The Night I Fell in Love With Dance Music: Danny Tenaglia

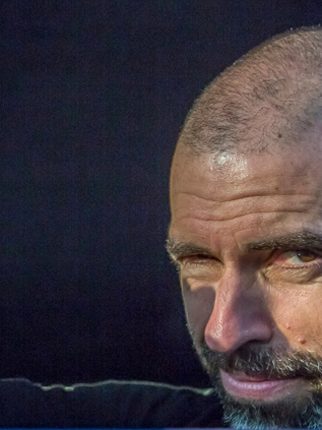

Danny Tenaglia is a legend—not simply because he has been playing 12-hour sets for nearly two decades, but also because those marathon shows have been cited as life-changing for so many dance music aficionados. Born in Brooklyn in 1961, Tenaglia first heard a DJ mix on an 8-track tape when he was 12 years old. “I knew instantly that that was what I wanted to do,” he says, “and I never turned back.” He began collecting music, honing his skills and getting involved in the then-robust New York City dance scene.

Seven years after hearing that first 8-track, he went to Paradise Garage and experienced the power and majesty of the iconic club. Indeed, he has not turned back since. Here, Tenaglia talks about that night.

Tell me about the night you fell in love with dance music.

I knew that I loved all this since I was a kid, but I think the night when it really hit home was when I went to Paradise Garage. I was a teenager, and I was already passionate about music and instruments and DJ gear. I had gone to other nightclubs as well and already had an addiction to the scene, but everyone kept telling me, “You’ve gotta go to the Garage.”

When I finally went, I was 19 years old. It just hit home. It was everything they all said it would be. What made it make more sense was that there was no liquor. It wasn’t your average nightclub; it was a dance party that was strictly about the music, and the only thing that I had ever experienced like that before was at the Loft with David Mancuso. That was a much more chill vibe than the Garage, in the sense that it was smaller.

Who were you with?

I was by myself, and I knew that I was going to meet people there, and I wanted to get there early. I remember the first song I heard there. It was very early in the night, and Larry Levan was playing the Peter Brown song “Do You Wanna Get Funky With Me.” I was mesmerized. There were still a couple of people on ladders, fixing gels and aiming beams. The lights weren’t down yet. There was really nobody there yet, maybe 20 people. I absorbed every inch of it. I remember planting myself in front of one of the big speakers and feeling that song and being mesmerized like a kid at Disney World.

Did you meet anyone?

The thing about the Garage was that there was a unity there. You didn’t necessarily have to know the people next to you; you just knew that they were Garage people. The thing about it was that there was this interaction between the dancefloor, the crowd and the DJ, the way people would dance and stomp and respond to lyrics when the DJ turned the volume down, and back then we knew the parts of the songs. We knew when it was about to take us to a higher high. There were also the performances. They sometimes had live acts there, and the crowd response to some of them—you would think you were at a Led Zeppelin concert at Madison Square Garden. People were going nuts. They had acts like Chaka Khan and Patti LaBelle, but also local acts with the hit song of the moment, and people responded to that just as if it was somebody huge.

How did being part of that affect you?

I learned from that. I learned how to feel what people were feeling. I learned how to play with an emotion that makes people feel what I’m feeling. It really was a school for me.

Did you dance?

Oh, yeah. The Garage had some amazing dancers, too. When I first went, it was a predominantly black, gay club on Saturdays. Then it started opening Fridays, and it was a more mixed crowd. I would go as often as I could on Fridays and Saturdays. It was all I wanted to do. I got my membership card in 1980. I was 20. I went religiously until 1985, but in October of ‘85 was when I moved to Miami for five years.

At the end of that first night, did you walk out feeling somehow changed, or knowing this was going to be your career?

Oh man, you’ve got me thinking about how many times I left there feeling all kinds of stuff. I was always absorbing the music that was played, and if I didn’t have it, or if I didn’t have access to it, then it was like being haunted. We didn’t have Shazam back then, and I really wanted to get my hands on those songs; quite often, it was stuff that only Larry had on tape or reel-to-reel, or it was a demo or something someone brought him, so you really had to wait to get these songs. It was kind of like a high. There was a famous record store nearby called Vinylmania, and I remember a few times staying up until the store opened just to see if I could get some of those songs that were played the night before.

How did this all correlate to what you went on to do in your career?

When I got to play Vinyl in New York from 1999 to 2004 was most definitely my version of Paradise Garage, because it was a non-liquor venue, so people were really coming for the music. It was midnight until noon. I did it for five years, every Friday. Once that club closed, all of the other ones had already closed by then—Tunnel, Twilo, Arena, Exit—they were all done. This is why I think Stereo [in Montreal] is my favorite club in the world. It’s a non-liquor venue, and you can play forever, and they really get it. The sound is amazing.

What are the advantages of a non-liquor club for you, beyond the fact that they can stay open longer?

The mentality of no bottle service, no champagne sparkles walking across the dancefloor. That’s what I like about Output in Brooklyn, as well. They have a no-camera policy and no reserved tables or bottles. Even though it is a liquor venue, it’s the best venue we have in New York right now.

Do you still get the same transcendent feeling you had that first night when you play now?

Definitely. It’s a feeling of just wanting to not mess up, because you want to give the people what they came for. You don’t want anyone to leave disappointed. You want to try and satisfy and please everybody. After playing for six or eight or 10 hours, people are really taking the journey with you, and you’ve pretty much satisfied everyone. That’s why I don’t really like short sets. The short ones are harder for me.

Is there one song that summarizes that first night out?

There are a few, but I still always feel that the one that carried it the most, even after the Garage closed, was a song from 1973 called “Love Is the Message.” It was the mother of all anthems, and many records came from that concept. If you listen to “Love Is the Message” and “Vogue” by Madonna, you can totally see the relationship.

When Nicole Moudaber discussed the night she fell in love with dance music, she said it was the first time she saw you. What is it like knowing you’ve provided that experience for people, and I’m sure more than one?

That’s what gives me the best feeling ever. I’m amazed at how many people send me such wonderful compliments like that and reminders of when they heard me here or there. It’s really humbling, and it takes me back to what I said to you earlier about what I learned from Larry. I feel like I didn’t so much learn his technical skills, because it was hard back then playing vinyl and album cuts and 45s—the mixing wasn’t so eloquent, but he made you feel what he was feeling. I think what people get from me is what I learned from him. They can really feel how much I love it. And now I need a Kleenex.

Follow Danny Tenaglia on Facebook | Twitter