New Book Documents Nearly 2 Decades of Burning Man Art

Cupcake Cars, 2006 Artists: Lisa Pongrace, Greg Solberg and the Acme Muffineering team.© NK Guy/TASCHEN GmbH

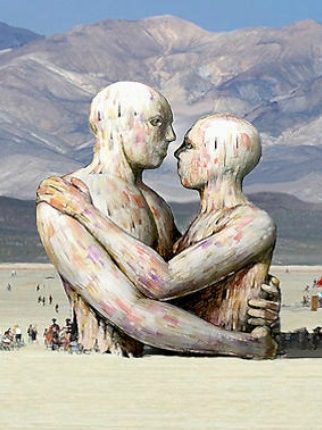

UK-based Canadian photographer NK Guy first attended Burning Man in 1998, and he’s gone almost every year since, shooting the dazzling art installations that populate the playa and help compose the event’s DNA. While the dust storms and high heat make shooting in the desert setting a logistical challenge, Burning Man’s otherworldly landscape lends itself to images that simply cannot be captured anywhere else.

At EDC Las Vegas this past June, the flame-throwing art car El Pulpo Mecanico and the ePOD spinning jungle gym both arrived from the playa, joining other art installations that have made their way to EDC after debuting at Burning Man. Similarly, Guy has introduced the art of Burning Man to new audiences via his book, The Art of Burning Man. Recently released by Taschen, the book features hundreds of Guy’s images.

Here, he discusses the project.

There’s so much to see at Burning Man; what was it about the art that made you hone in on that particular aspect?

There are two things. First, the transience of it: It’s just amazing that so much of the art is gone forever. The pieces made of wood will never be seen again, as it’s all consumed in flames. But even the stuff that’s not—the steel stuff and so on—will never be seen again in that particular context. And that brings me to the second point, which is that it’s such a fantastic and surreal experience; to me, it’s like walking onto a movie set of another planet, and no one really experiences that in everyday life. There’s always that sense of the mundane mixing with the magic and mysterious, and that’s what interested me—the scale of it, the interactivity of it. It’s not just, “Here’s a thing on the wall you can’t touch.” It’s more like, “Here’s a giant thing you can explore,” and those are all elements that make Burning Man art completely transformative for me.

You’ve been going since 1998. Have you observed an evolution in the art throughout the years?

It’s certainly become a lot bigger, and there’s been a huge budgetary increase in the art at the event; the infrastructure to make [the art] has also changed. In the early days, there was more stuff at either an individual level or a small team level. But now there’s this cultural tradition, and also the building of infrastructure in San Francisco, the Bay Area—Oakland and Berkeley—and also places like Reno, Portland and Seattle. There’s been the development of an infrastructure to build stuff at a community level. And that’s really changed things.

Man Burn, 2013 Artists: The Man: Larry Harvey, Jerry James, Dan Miller, and the ManKrew. Man base: Lewis Zaumeyer and Andrew Johnstone. © NK Guy/TASCHEN GmbH

The temples are a huge step in that direction. David’s first temple in 2000 was just him and a few friends. It was the size of a two-car garage; I remember seeing the piece burn, and it was cool, but it wasn’t the size of a giant office building, like the temples are today. Also, stuff has changed technologically; electroluminescent lighting and LEDs are now everywhere, which means you can do more subtle stuff with light that you couldn’t before. With a couple of batteries, you can run all these very elegant light displays all night long. In the past, you had a generator buzzing away with a big spotlight, and that was not terribly subtle. The development of flame technology has also been amazing. In the past, there’d be a propane tank with a couple of flames; now they’re these computer networks controlling individual flame effect devices that let you trigger off individually controllable explosions that the participants can actually trigger. So there’s been a lot of change over the years.

Do you have an image that’s particularly special to you?

A really memorable one was a shot I took in 2000, of the man. I’d gone out with some friends; we’d done a photo shoot in the middle of nothing with infrared film, and we’d finished, and the dust storm had kind of rolled in that afternoon. We were heading back to camp, and we got separated in the dust. I was kind of blundering my way through. This was 2000, and in those days, I hadn’t learned to navigate. I was thoroughly lost. Then suddenly, I realized I was at the back of the man. In those days, the man didn’t really have a base; he just sort of stood on a little pyramid of hay. There he was, and just for that moment the clouds parted, and there was this perfect view of the man. I lifted up my camera, and I was using a red filter, because I was using infrared film, so all I could see was this bright expanse of red, with this this silhouetted man in the middle of the frame. I thought, “Okay I’ll give this a shot.”

Those days, rolls of film had 36 shots, and luckily there was one frame left, because every now and then you would get 37 shots out of a 36 roll of film. I pushed the shutter and heard the click, and then the camera started to rewind. That was the last frame on the roll. It was the most perfect moment; within seconds the clouds closed, and I couldn’t see the man anymore. I was pretty sure it was a good shot, but with film you never know until you get it back from the lab. I got the film back, and it was the most astounding picture. It’s a black-and-white shot that I used to close the book, next to the contributing credits. For me, that’s a special moment—partly because it was absolute luck to encounter that—but also, it reminds me of the sort of magic that you get at Burning Man. You could be having this horrible time; you’re choking on dust, and you don’t have a dust mask, and you’re out there, and it’s just nasty, and then magically you encounter something you didn’t expect.

The Temple of Transition, 2011 Artists: David Best and the Temple Crew © NK Guy/TASCHEN GmbH

Are there pieces of art that have stood out for you throughout the years?

I would say the temples as a whole—not one specific temple, but the temples as a collective. In a way, it’s like each temple is the same temple, because each one has the same goal and purpose; yet each one is completely and utterly different. Each one is made by a different artist; David [Best] did about half of them, but others have come and done their own spin on it. They’ve quite often used different materials and types of construction, and yet as a collective work, I think it’s so remarkable that here’s this festival—and people think of festivals as party time—and there’s this temple dedicated to a universal human experience that everyone can relate to and that everyone becomes part of. That’s just something you don’t find anywhere else.

Black Rock City, 2011, City plan by Rod Garrett, © NK Guy/TASCHEN GmbH

And those temples are obviously structurally glorious, but they’re also so important and special because of what everyone brings to them and the sort of collective effort to make them so sacred.

Absolutely. I describe them in the book as a sacred secular space, in terms of it not having any specific religious belief system or enforced belief placed on it. Instead, it’s what people bring to it that make it such a powerful experience. For some people it’s religious, for some it’s completely free of any religious impulse, but it’s certainly a personal human impulse. Whatever it is that you bring, it’s what you experience, and that’s what makes it so powerful.

A lot of Burning Man art has subsequently appeared at other shows and events, including Insomniac’s. Do you have any thoughts on the art of Burning Man being seen in other, more mainstream, contexts?

One of the things I find quite interesting is the spread of regionals. I’ve been to Nowhere in Spain; I went to the second one in 2005, and it’s grown considerably since then, and in other areas as well. Same with Vancouver—I was involved in the first recompressions there. They don’t call them decompressions, they call them recompressions because you’re supposed to recompress. Those were interesting, because they all start with an impulse to hang on to something you experienced at Burning Man, but then they sort of move into a different direction and take on their own life, and people start bringing aspects of that event into these regional events. It’s certainly an interesting thing to see.

El Pulpo Mecanico, 2014 Artist: Duane Flatmo and Jerry Kunkel © NK Guy/TASCHEN GmbH

When you see art that originated at Burning Man in other contexts, it can be interesting to see how that works. Sometimes it can be that the magic is gone. You look at it and go, “That’s kind of crap. It looks cool in the desert, but here it looks like a bunch of junk.” Other times, you see a piece and you think, “Wow, that’s a spectacular piece regardless of where it is. If it happened to be in an empty desert that’s pretty cool, but it still holds up outside of that.”

What’s something that anyone who hasn’t been to Burning Man should know about the festival?

There’s this weird preconception a lot of people have that it’s all these naked hippies partying, and if you’ve been to the event, it sure as hell isn’t that. It’s such a complicated event with different social threads and social traditions, and there are people you could call hippies, but they’re certainly not dominant at the event at all, at least not from my point of view. Not that there’s anything wrong with hippies.

It’s like going to a country you’ve seen only in a postcard and thinking, “Okay, I know what this place is like.” Then you go there and realize you really don’t know it at all. There are these strange cultural traditions you kind of have to learn, and the physical conditions are very challenging and harsh. Anyone that goes for their first time needs to be encouraged to be aware of that and be open to the experience around them.

Katie Bain thinks everyone should go to Burning Man at least once. She’s on Twitter.

Follow Insomniac.com on Facebook | Twitter