EJTech and Their Sonic Secrets

After we posted about EJTech’s amazing art a little while back, we couldn’t get the genius of it out of our heads. So we decided to have a chat with Esteban de la Torre and Judit Eszter Karpati, the duo behind EJTech, to learn their sonic secrets. We delved into the origins of their work, the innovative materials they use to make their pieces, and their mutual love for music and manifesting it in beautiful physical forms.

Esteban and Judit answered as team, unless otherwise noted.

“Textiles and music have so much in common…Electronics are the alchemy that holds it all together.”

Tell us a bit about how you guys met and your partnership as EJTech.

EJTech is an experimental art and tech lab based in Budapest, Hungary. We met when we both started at MOME (Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design) in Budapest. There were instant sparks, but just about a year ago, we decided to establish EJTech. It just felt natural to help each other with our own projects. Then we started to test combining our art mediums. That worked out so good, we had to take it seriously.

What were your focuses of study? Esteban, let’s start with you.

Esteban: I’m an audiovisual artist and technologist from Mexico. I work across both visual and sonic media, exploring tangible interaction and further dimensions in technology. I’m addicted to tweaking knobs and altering functions of ordinary objects, hacking, audiovisual performer, and I’m a Nintendo fundamentalist.

How about you, Judit? I understand you cover the textile side of things?

Judit: Yes, I’m from Hungary, and I’m a textile artist and researcher in the field of e-textile. My main research is focused on the integration of interactive technologies into textile art, connecting the mediums together, creating cross-platform situations.

After you started working together, what made you decide to combine music, electronics and textiles?

The inspiration came from our love for all of those subjects. It’s like we put them all in a blender and hoped the blender wouldn’t break—or that it would break but sound really good. Textiles and music have so much in common: texture, pattern, rhythm and electronics. Electronics are the alchemy that holds it all together.

In terms of the textiles, what goes into making them? Do you make them all yourself?

We work a lot with neoprene, silver yarn, copper weave, and other conductive materials—those we have to fish from technical textile manufacturers. This is where you get the threads for firemen’s anti-spark coats, cut-resistant gloves and space wear. Of course, we also work with more accessible and everyday classic fabrics—cottons, canvases and such. We hacked our own KH-910 electroknit knitting machine, so we knit our own; then we take all those items and build our pieces from scratch.

I don’t hear a lot about textiles in the art world. Can you tell us about where they stand?

When working with textiles, it’s important to think outside the box. You can weave a textile out of 10,000 teaspoons and end up with a gorgeous stable structure. That is considered a textile, too. Usually when people think about textile, they picture a dress. We think this is one of the main reasons “textiles” are not so relevant in the art world and stay boxed into the fashion world. Nowadays, more exhibited artistic textiles are popping up. It might be a thin line now, but it is widening.

That’s kind of where you come in with some of your projects like SoundWear, right? With these pieces, you can widen that line.

Esteban: Exactly. SoundWear was chopped, boiled and spiced during a six-month grant program at an innovation lab called Kitchen Budapest. Basically, we took Faraday’s law of induction and embedded it onto a wearable piece of clothing. During these six months, we were experimenting with the intersection between textile and sound and the idea of touching sound, and of course vibration was one of the most sensible directions to take.

Judit: You get emf (electromotive force) when a magnet interacts with an electric circuit, like the copper in the clothing. Then you just plug in your 3.5 jack and run a low frequency through it, put it on, and you’re wearing bass!

How does the design of those pieces change the sound?

It’s actually really interesting how different sounds react to the patterns we came up with—some sounds are far more efficient on intricate, thin designs—and how the shape of the circuit reacts to high versus low frequencies. We ran everything through it, from a sine wave, to roots dub, to Berlin contort techno; they all yielded something different.

Do you plan on marketing SoundWear?

We don’t have any plans yet on going big with SoundWear. We thought of maybe collaborating with a music festival or band for promotional tote bags, or a limited line of T-shirts for the release of an epic album, but we don’t know yet.

What out there inspires your pieces?

Inspiration is everywhere. Sometimes eureka moments come while you witness how soap bubbles are formed while washing dishes, or while whistling an old chain gang spiritual… maybe even while thinking about the green war room table in the classic Dr. Strangelove. EJTech has two halves, and the constant ping-pong of ideas between us is what boils down our very distinct skills into a common potion.

“We couldn’t get over the idea of taking off your scarf, plugging it in, and jamming hard on it—then unplugging it, wrapping it back around your neck, and heading out the door.”

How about music? Obviously, that’s a large part of your inspiration.

Esteban: That’s a hard question. We love music. While working, we usually listen to Daisuke Tanabe, the Books, Knxwledge, Murcof, maybe some Bossa. Judit is a big Ryoji Ikeda and Autechre fan.

Chill choices!

Judit: Yeah, and Esteban is into Aquarian Foundation, Torn Hawk, Raime, Oneohtrix Point Never and Delroy Edwards—but still showers to MF Doom. Usually, we just keep “Epitaph” from Castlevania III on repeat—for days!

Back to another one of your projects: that MIDI board. How on earth did you make that awesome thing?

One of the main ideas for the MIDI board was to completely maintain the foldable, flexible properties of textile. We couldn’t get over the idea of taking off your scarf, plugging it in, and jamming hard on it—then unplugging it, wrapping it back around your neck, and heading out the door. We used cotton canvas and screen print only. It all plugs into a micro-controller. From then on, it is up to the user where to plug it. We used Max/MSP and Live; but it could even be connected to, let’s say, Resolume for creating visuals, or even an old Nintendo emulator for breaking bricks in a Mario game!

Is that part of your goal—to bend music and bring it to the physical word?

Definitely. It is part of our goal to make sound physically tangible. The instruments we use have a direct effect on the final outcome of our intent, like playing a piano with chopsticks versus using bowling pins. One of the most exciting things about this technology is the unlimited number of ways you can personalize it—from the size of the pad, to the shape and length of a fader, and so on. There are unlimited possibilities. It’s also worth noting that these textile controllers won’t break if you drop them, or short if you spill your beer on them. Because it actually has zero parts, it really can’t go wrong.

Since one of your goals is to meld the physical with the sonic, how do you feel about physical records?

Judit: We are big fans of music in its physical form, like vinyl or cassettes. Watching a vinyl spin and how it works is beautiful. I remember [Esteban] sitting on the subway as the batteries in my Walkman died, and popping the lid open and watching how the cassette literally slowed down. It’s the simplest manifestations of sound in the physical world, yet so pure and raw. It’s magic.

What about digital downloads or things like Spotify? Would you rather be able to hold your music in your hands and sort of feel it the way you can touch fabric?

We are not really into Spotify or digital downloads, although they do have a huge pro: The amount of music you can find is endless. At the same time, nothing will ever beat buying a new record, putting it on, reading its sleeves and booklet, and displaying it around your turntable because it’s got gorgeous cover art. That record becomes yours, [as opposed to] a download you will never feel truly belongs to you. Maybe that’s because you never get to clean dust off of it.

How about your Chromosonic project? That seemed to be one of your first real marriages of all these mediums. Can you give us a rundown of how that was made?

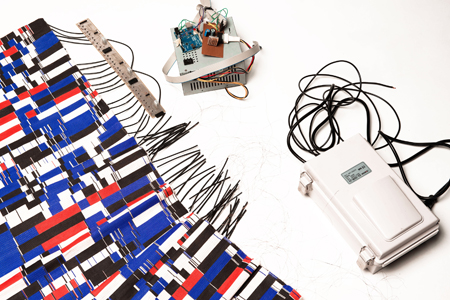

Esteban: The idea behind Chromosonic was to create a flexible display only made from textile. It was actually Judit’s diploma work at the university. In many ways, we are glitch fundamentalists, and she decided to go with a glitched-out monitor aesthetic for this project. There are wires woven into the fabric that cause the dynamic dye to react and change color. These wires are again connected by a micro-controller that is responding to sound. We are currently working on a costume interface to control it for a real-time audiovisual experience.

It turned into such a beautiful project. Where else do you want to take this collaboration?

EJTech is just a sprout at the moment; soon enough, it will be a full-on jungle with Mayan temples and all. In the near future, we are working on hula-hooping with the light spectrum and sonochromatics. We also have immersive soundscape in the works for our screen-printed technology. We are pretty psyched!

Follow EJTech on Facebook | Twitter | Instagram